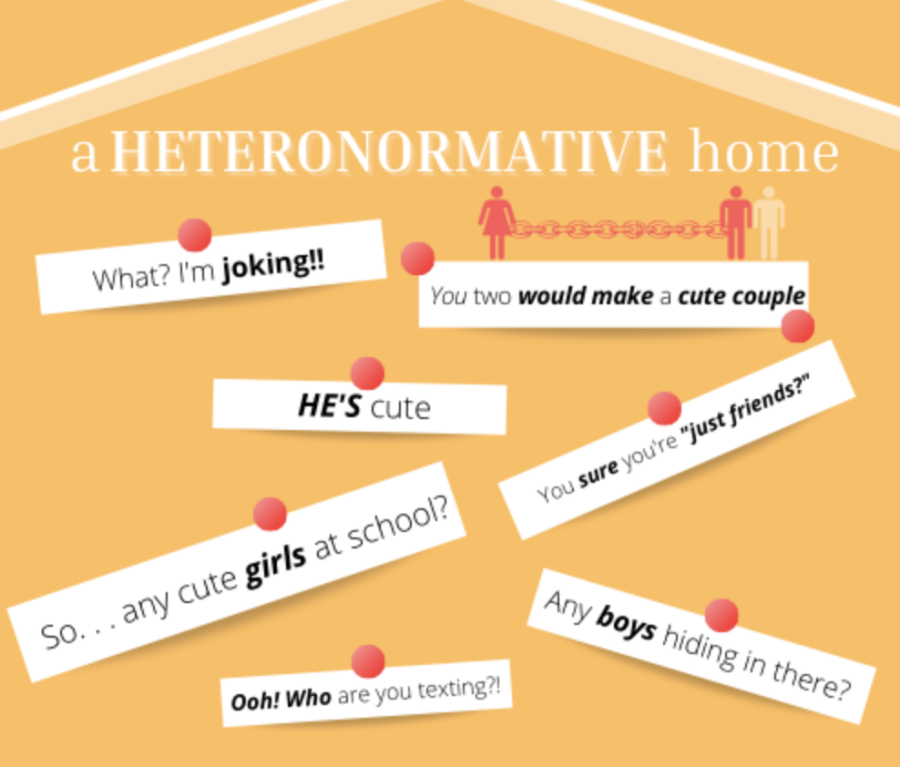

The damaging effects of: ‘I’m just teasing.’

The socialization of heteronormativity at home has a significant impact on children, becoming more apparent in their teenage years.

There was a lot of teasing in my household accompanying any conversations about boys and relationships. It was clear to me that when my dad would jokingly warn, “There better not be any boys hiding under your bed,” or when my mom asked if I thought any of the boys in my grade were cute, that there was an assumption and expectation that I would be straight.

As it turns out, they were right, but that really isn’t the point.

When parents assume their children’s sexual orientations, or put pressure on making cross-genered friendships develop into romantic relationships, they are reinforcing a damaging heteronormative practice that can be hurtful to both straight and queer children.

According to Pierre Bourdieu, a former French sociologist and author of “The Logic of Practice,” what parents say and do in reference to sexual identity and relationships has a psychological effect on all kids.

I remember when I started middle school and had developed a crush on a boy. In getting to know him from a distance, I saw that his friend group was co-ed; I was shocked. It was so unusual to me to see a group of girls and boys who were all “just friends.” As a result of my upbringing, and the lessons I absorbed from my parents, the only explanation that made sense to me at the time was that they all subconsciously like-liked each other.

“How do boys and girls even become friends?” I questioned. I assumed their differences in gender would prevent them from having much in common and could only end as a romantic relationship.

When I got to high school, I began to recognize this mentality as a legitimate issue. I realized how the years of “playful” jokes and “harmless” inquiries about everything boy-related at home had affected my ability to comfortably socialize with half the student body. It didn’t matter if I liked them or not; I was burdened with immense anxiety just because of the fact that they were a specific gender.

Emphasizing gendered friendships, or rather failing to normalize cross-gender friendships, isolates kids in same-gender peer cultures, which can lead to romantic difficulties in future relationships, as suggested by Marion K. Underwood and Lisa H. Rosen in their manuscript “Gender, Peer Relations, and Challenges for Girlfriends and Boyfriends Coming Together in Adolescence.”

“Children spend substantial time in these contexts and socializing mostly with peers of their own gender may lead to challenges for forming other-gender relationships.”

By parents of LGBTQIA+ children presenting heteronormative behavior and perceptions to their teenagers, they are in turn perpetuating this negative self-image, creating cause for matters such as suicide or depression.

— Anna Diorio ’23

In the past few years I’ve learned to resist this heteronormative culture, but my frustration with it has only grown. It’s frustrating when my family or other adults constantly ask if I am dating a male-friend of mine—when I am pushed into viewing my friend in a romantic way. It’s frustrating when I have been accustomed to separating people by their gender instead of the unique, individual traits they have as people. And it’s frustrating when, in a time where I am still discovering my own identity in a daunting world, there are restrictions on my freedom to do so. I’m straight, but it is my right to still question my sexuality and keep figuring out who I am.

For closeted LGBTQIA+ adolescents, especially, the assumptions of being heteronormative may be even more difficult to deal with, given the increased fear of not being accepted or understood by their family. While I cannot directly speak for LGBTQIA+ adolescents, research shows that it internalizes negative perceptions of “non-heterosexuality” in these individuals, specifically.

“LGB children often worry that their parents will not love them anymore or that their relationship with their parents will drastically change,” according to Caleb Lawson, B.S., B.A. in “The Effect of Heteronormative Socialization on Beliefs, Attitudes, Perceptions, and Behaviors.”

Children are strengthened by parents who are supportive and accepting. When children know their parents will love and support them no matter who they date, they will automatically develop the strength and thickness of skin needed to face a world that might be less accepting.

I’m not implying that my parents are evil or entirely to blame for increasing my anxiety about forming relationships with boys. But no matter who or what is to blame, damage in trust has occurred.

The romantic comments I endured that magnified every relationship or reference to a boy I know certainly has put a strain on my relationship with my parents. When I actually am attracted to someone, I won’t want to turn to people who, in the past, made me feel uncomfortable about having relationships. I wouldn’t want to be teased. I would likely be nervous and want to seek comfort and guidance in navigating such a new experience from someone who would be supportive and non judgemental.

I understand that I am sharing personal information about myself—and I admit that I was apprehensive about doing so. But when I brought up this idea of parents teasing and romanticizing every reference to the opposite sex to many of my peers, I quickly realized that this issue stretched far beyond the front steps of my house and demanded to be heard.

Broadcast Director Anna Diorio ’23 entered Staples deeply hoping to become a part of something in the school community. Inklings proved to be a place...