Despite consequences, edibles prove popular

*Names that have been changed

Sitting in her social studies class, a senior girl raises her hand to ask her teacher if she may go to the bathroom. Hands in her pockets and head lowered, she enters the girls’ bathroom and checks to see if the stalls are occupied. Empty – she’s set.

She pulls a homemade cookie from her pocket – a cookie that is nothing like the ones her mom used to make – and takes her first bite.

Adrenaline pulses through her veins, and she washes the cookie down with a swig of water. Gone, without a trace of evidence. She then returns to class and anxiously waits for the high to kick in.

In this scenario, similar to one described by an anonymous senior girl, the student has just eaten a cookie baked with marijuana, a concoction commonly referred to as an edible. In addition to cookies, brownies and lollipops are also popularly laced with the drug.

Some people feel that this form of drug has “always just kind of been there,” as one anonymous senior girl, Haley*, said. However, Max Wimer ’15 has noticed an “increase of usage in people wanting edibles” in the last few years.

Another anonymous senior girl, Laura*, noted that edibles are “big at Staples, but they’re also big in Fairfield County,” she said. Laura thinks that it’s because “kids have the money to just dish out on edibles.”

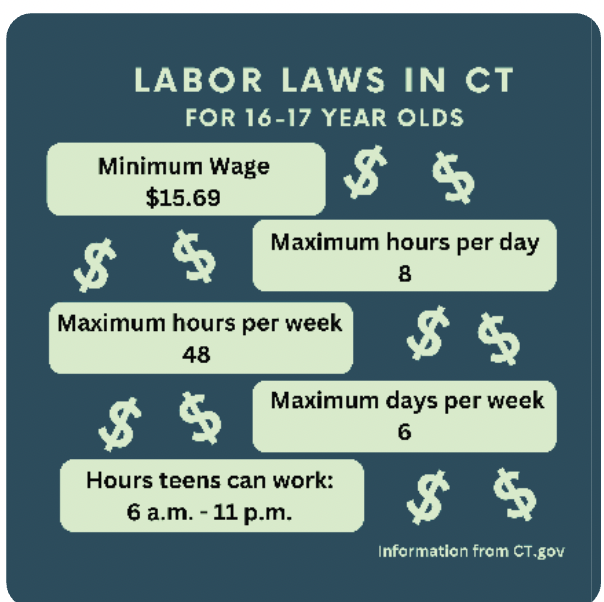

An edible typically costs around $20, which is slightly more than the cost of plain marijuana because, according to an anonymous senior boy, “you’re paying for the weed itself and the preparation of the edible.”

As for the rise in sale and consumption of edibles at Staples, Wimer credits the relative ease in acquiring them and the lack of suspicion eating an edible incites.

In Connecticut, medical marijuana is legal and the drug has been decriminalized since 2011. But possessing at least one-half ounce of marijuana can elicit jail time and a fine. Selling or having the intent to sell the drug, regardless of the amount, can land a first offender in jail for up to seven years and can possibly include a fine of up to $25,000.

Despite the legal consequences, students continue to consume edibles, even before or at school.

Haley admitted to both smoking and eating marijuana before school.

“Doing an edible hits you harder [than smoking] because you don’t come to school high, and you’re just sitting in class, and then you’re like—f—,” she said.

Once, when she did an edible at school, Laura recalled how she couldn’t stop herself from falling asleep. “I was so tired, [so] I skipped a class, and I was just, like, shoot, I got to go sleep because I was really just not going to stay in class,” she said. “I was about to pass out, so I just slept in the auditorium.”

Principal John Dodig acknowledged that students like Haley and Laura are nothing new.

“I’ve been at this for 47 years, and the behavior has not changed one iota. Kids do risky things,” he said. “It is much better now, but our job is to, in a calm way, prepare kids to make good decisions. We have health classes, for example, but if something goes wrong, we deal with it in an unemotional way so that we don’t upset other people.”

The consequence for distributing edibles at school is expulsion for up to 180 days and consuming an edible can lead to a suspension for up to 10 days, according to Dodig.

Isabel Perry ’15, co-President of TAG, explained that “what makes edibles so dangerous is that a lot of times people don’t know the exact ingredients or the amount. It’s that uncertainty that can lead to unwanted situations.”

However, some students don’t fear these consequences of consuming an edible or getting caught.

“You can’t get in trouble,” Laura said. “There’s no evidence you ate it. It’s gone. If you don’t tell anyone, no one knows.”

On the other hand, Haley did acknowledge that there are indicators that a person has done an edible. “You get all the [same] symptoms [as smoking marijuana], like my eyes are shot red, and you forget everything,” she said. “But Staples is a great school, and a lot of people have Visine.”

Haley and Laura deemed the difference between eating and smoking substantial.

“When I smoke, it’s never the right amount,” Haley admitted. “It’s either I literally die or like I’m not exactly high, but I’m on the brink.”

Laura continued to say, “You don’t take an edible and not get high; that’s not an option.”

Haley also considers edibles more appealing than smoking because there is no smell, and “it’s hard to find a place to smoke. With an edible, you can just eat it.”

While Wimer believes that the drug culture at Staples is “fairly representative of the drug culture around Connecticut,” he acknowledged the presence of a preconceived notion about edibles among the student body.

“[There’s a] stigma that if you smoke and come to school high, you’re a bum, a stoner,” he said. “But in my mind, you’re a stoner if you let smoking weed affect your daily life and process. If you smoke and can maintain what you need to do daily, then it’s not a big deal. But there will be a stigma attached to it no matter what.”

Editor-in-Chief Bailey Ethier ’15 has self-described himself in one word as “Texan.”

Growing up in Texas, Ethier dreamed of being a professional...

When she first joined Inklings her sophomore year, Jane Levy ’16 was scared to raise her hand in class. She lacked confidence in her voice and her skill....