Andrew Yang’s call for Asian Americans to demonstrate patriotism falls short

Today was the day. After several days locked in quarantine in the shelter of my home, I was finally going to step outside and enjoy the fresh air. But as I strolled through the familiar streets, suddenly my neighborhood morphed into a foreign landscape. I was conscious of every step and every breath I took as passersbys skittishly picked up their pace or glanced at me with an uneasy wariness.

In an opinion piece published by The Washington Post, former Democratic candidate Andrew Yang called for the Asian American community to stand up against the recent rise of discrimination as a result of the coronavirus outbreak on April 1.

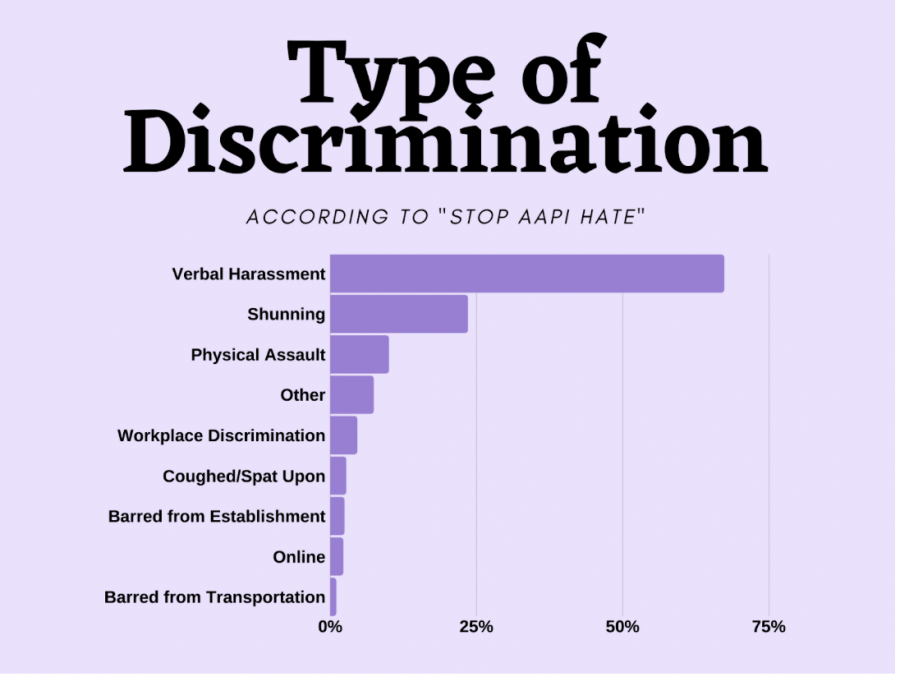

“For the first time in years, I felt it. I felt self-conscious — even a bit ashamed — of being Asian,” Yang said. From pushing, to spitting, to stabbing, the amount of news reports on targetted discrimination appears to be ceaseless.

As one of the few Americans of Asian descent to run for president, Yang encourages the Asian American community to embrace their “American-ness” now more than ever.

Yang underlines the reality that simply yelling ‘don’t be racist’ is not effective. “So, in lieu of adopting a posture of outrage and victimhood, Yang instead looks to rise above it,” Spectator USA journalist Melissa Chen said.

Indeed, it is difficult to alter stereotypes of racism that is so heavily ingrained in centuries of history. But in his statement, Yang failed to denounce the already-brushed-over history of Japanese internment camps during WWII. Instead, he oversimplified his call to action by suggesting that it can all be fixed by simply wearing red, white and blue.

I don’t need to earn my badge of “American-ness” that I should already have through meaningless acts of patriotism. Volunteering at annual blood drives or singing the national anthem at swim meets doesn’t stop people from unabashadley asking me where I’m “really” from.

If the coronavirus does not discriminate amongst different races, then why is one race being restrictively encouraged to help more than other groups? In doing so, this only further isolates and singles out the blame on the Asian American community to take responsibility. Every single American, regardless of skin color, should be held just as liable to support their small restaurants, donate to food banks, and support neighbors.

Albeit Yang’s implications that Asian Americans are less likely to contribute, they have been actively leading as an example of supporting local hospitals and organizations. If anything, local Asian communities are volunteering on the frontlines to aid health care workers and donate personal protective equipment (PPE).

Especially since the majority of PPE is manufactured in China, many are starting successful fundraisers through WeChat to connect with relatives and businesses in China. For instance, Chinese Americans raised nearly $20,000 to supply more than 5,000 surgical masks to the Danbury Hospital. Yale New Haven Health, the fourth largest system in the nation, received nearly 10,000 KN95 masks donated by groups like the Yale Chinese Parents Club.

Despite these efforts to tear down subconscious biases, attacks on the Asian American community are not going to stop anytime soon, nor should they be normalized under the “model minority” assumption. Especially when Asian American representation is rarely highlighted in Western media, it’s disappointing to see that Yang’s stance panders to that narrative.

This alarming trend is no doubt fueled by the harmful and misinformative rhetoric used by government representatives. Rather than using scientific terms such as “Covid-19” or “coronavirus,” leaders instead talk about the “Chinese virus” or the “Kung Flu.” Encouraging these selective terms only heightens the tendency to clump stigmatized Asian features as threatening.

Unlike what several world leaders may perpetuate in their misleading information, the coronavirus is not exclusive to race, as it has since spread indiscriminately to almost every continent in the world. USC professor Natalia Molina points out that we’re still more worried about someone who looks Asian coughing into their shirt than about understanding best practices to stop the spread.

Despite his awkwardly worded op-ed, Yang sheds light on the need for strengthening the social fabric of this nation. The rising prejudice both online and in-person against Asian Americans today eerily echoes back to the incessant targeting of Middle Easterners after 9/11. Don’t let history repeat itself.

If America wants to come out of this pandemic as a more united nation, we need to take condemnation a step further and educate people on the roots of their perceived stereotypes. That starts not by constructing a wall of hostility and bitterness, but by everyone pitching in to create productive discourse.

Serena Ye ’20 is a web arts editor for Inklings. Ye took Advanced Journalism because she enjoys how journalism can cater to all different types of people,...