In the midst of her freshman year, Chloe Pflug ’13 was cut down by a vengeful entity. The culprit? Common illness.

As a result, she missed not only various homework and in-class assignments, but Spanish and Geometry tests as well.

Upon her return to school, Pflug says, she found that both teachers for her Spanish and Geometry classes were “demanding,” as she put it, she immediately take the missed assessments, despite the fact that she had ample makeup work in her other classes as well.

Pflug took her Spanish test before her Geometry test. Her math teacher then asked her why she would put the World Language department before her Geometry test, putting Pflug in what she called “an awkward position.”

Although Pflug holds that she has “nothing against either department,” she now feels that teachers often do not understand that students have numerous priorities spread among all their classes.

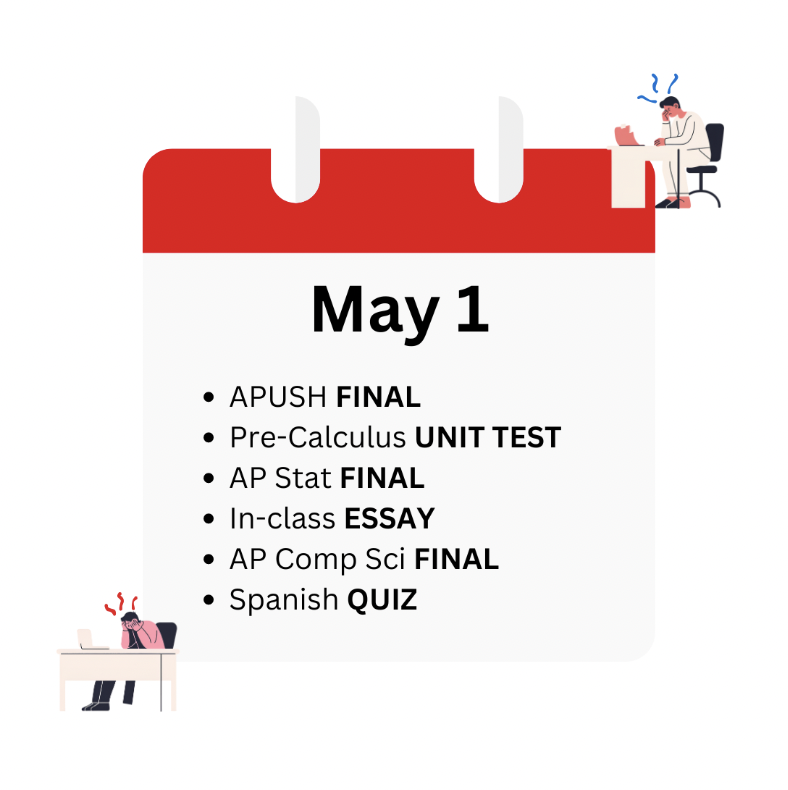

While most Staples students have not been placed in the same situation as Pflug, her experience is a microcosm of the discrepancies that can arise between teachers and students with regard to taking assessments later than assigned. Because there is no uniform test-taking policy at Staples, some students may find it complicated to arrange times to make up multiple assessments for different classes.

According to James D’Amico, the 6-12 Social Studies department coordinator, it is a requirement for teachers to publish a late test-taking policy in their course syllabi “so that students are aware.”

And although some students like Pflug may encounter tricky situations, many believe that allowing teachers to decide late test-taking policies for their own classes is reasonable, due to the fact that each student who takes a test late usually comes with a different story.

“Absences can happen for many different reasons, whether it be a sickness or a vacation, or a doctor’s appointment or whatnot,” Matt Hodes ’13 said. “I think late test-taking should be dealt with by the teacher so he or she can personally alter the amount of time he or she gives.”

Shweta Lawande ’12, who admits to taking “many tests days after they were actually given,” also thinks that teachers should be able to change the late test-taking policy in their syllabus to their liking.

“Teachers take into account the fact that oftentimes, a student will have missed more than one assessment in multiple subjects and is struggling to make those up as well,” Lawande said. She adds that it is “incredibly helpful” when teachers work with students to coordinate their schedules.

Some students may abuse the privilege of a teacher’s late test-taking policy; however, English teacher Jesse Bauks feels that it is the teacher’s responsibility to recognize when this is being done.

“If a teacher knows his or her students well enough,” Bauks said, “he or she should be able to recognize whether or not a student is or is not taking advantage of the makeup time given per the teacher’s policy.”

Mathematics teacher Gertrude Denton echoes Bauks, and believes that it is the teacher’s duty to apply their late test-taking policy “fairly and consistently.”

Denton, whose policy requires students to take a missed assessment during class upon their return to school or during a free period before their next class period with her, recognizes that some of her students may not be happy with her policy.

“However,” she says, “my obligation is to get tests back to students as soon as possible, and I am always trying to narrow that timeframe. I don’t want to have to hold on to tests longer than I should.”

Though English, social studies, math and science teachers have the ability to customize their own late test-taking rules, those who teach a World Language class have to comply with a department policy.

During the 2008-2009 school year, the World Language department set a standard syllabus to be used by all language teachers, according to Spanish teacher Renee Torres. This means that any World Language student—no matter the teacher nor the language—who misses one or two days of school has a full school week to make up a missed assessment.

Spanish teacher Ana DeLuca says that the policy’s chief purpose is to ensure fairness and consistency throughout the department.

“We took many things into consideration so we can work well with all of the students,” DeLuca said. “And if you miss a test or a quiz, we can give you as long as you need, but the sooner, the better, for your own good.”

Kaitlin Fontaine ’14 finds this departmental divide to be detrimental to a student’s success: “World Language shouldn’t be able to have their own rules that are different from the other departments, because it makes it inconsistent for all of the different classes that students take to complete assessments that they miss when they need to.”

Nevertheless, DeLuca justifies the unique World Language syllabus: “It’s all good, as long as it is working for all of the students,” DeLuca said.

Weldon • Nov 16, 2011 at 1:44 am

I found the information on this site valuable.