Guantanamo Bay, other issues command youth advocacy

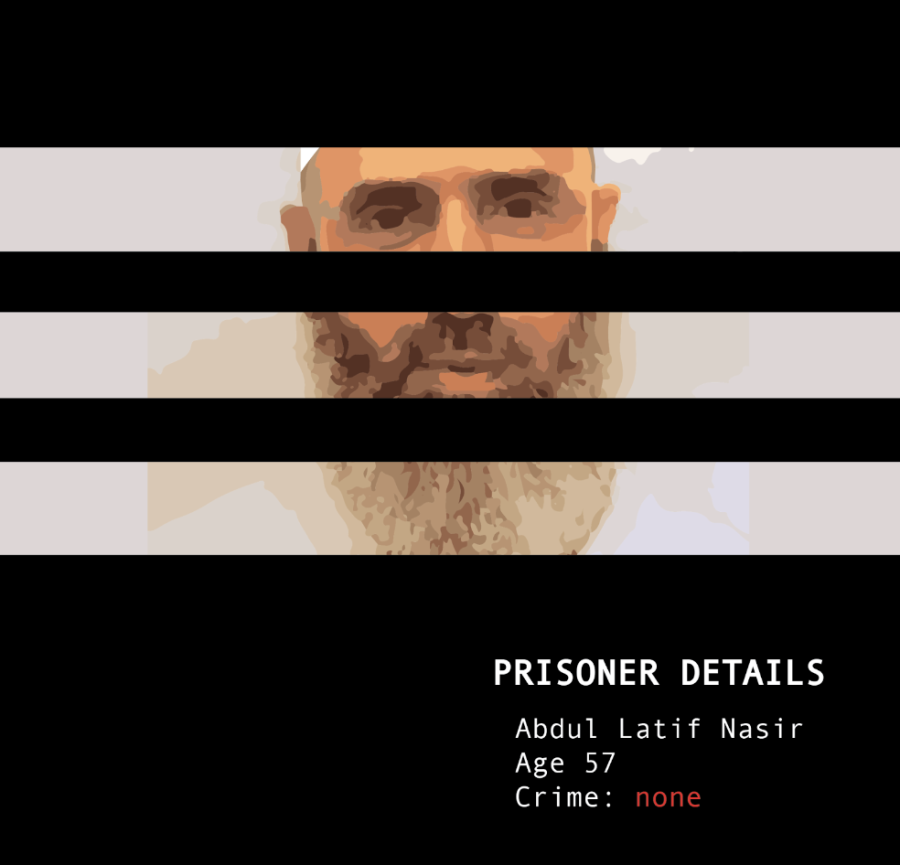

Abdul Latif Nasir, a man never convicted of a crime, was released from Guantanamo Bay on July 19, 2021. Today, 35 detainees still remain at the prison.

Guantanamo Bay.

U.S. military base.

Detention center.

Site of torture.

While there has been more scrutiny in recent years, the conditions at Guantanamo Bay remain largely concealed by the American government. Leaked reports and investigative journalists have illustrated a prison where gruesome abuse is rampant and human rights are completely disregarded. Since its inception in 2002, nearly 800 Muslim men have been detained here—nearly all of them without trial or charge.

In September, my Contemporary World Studies teacher asked my class to research 9/11. As I studied the American response to 9/11, my research uncovered the story of Abdul Latif, a man wrongly detained at Guantanamo Bay for nearly two decades. His story compelled me to write about him in our next class project: a letter to the White House. It also made me aware of how my role as a student allows me to advocate for those who cannot speak for themselves.

After 9/11, the U.S. waged war on Afghanistan, where Al-Qaeda and Osama Bin Laden had orchestrated the attack from. In the lead-up to 9/11, Al-Qaeda had started to recruit young men into training camps where they would receive basic military training. Nearly all of the men were unaware that Al-Qaeda was planning any kind of military offensive. Many of them attended the camp simply to learn how to protect their families in regions of instability. Others saw it as an opportunity for self-development. However, when the U.S. turned to Afghanistan, they threw all the on-ground fighters into Guantanamo Bay without determining if they were actually guilty. Abdul Latif was one of these men. He was never charged with a crime and his federal documentation explicitly states that he did not agree with the attack on September 11, 2001. Yet, he was still punished because the U.S. associated all of these men with extremists in relation to an attack they were not involved in. By doing so, the U.S. violated the Geneva Convention and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

At Guantanamo Bay, Latif was subject to the psychological and physical torture inflicted on all prisoners. Waterboarding, force-feedings, sleep deprivation and beatings are only a few of the methods the U.S. has employed at the facility. While Latif was eventually cleared for release in 2016, Trump’s rise to the presidency halted this process. Trump declared that no detainees from Guantanamo should be released, and with that, Latif’s hope for liberation was again diminished to nothing.

Only last year, when the Biden administration came to power, was Latif finally released to his family in Morocco—19 years after he entered Guantanamo Bay. Upon his release, Latif wrote a letter in which he said nothing of the brutal atrocities committed against him. He wrote simply of his joy at his release and the opportunity to see his family for the first time in decades.

“When I get out of here and my foot touches the ground in Rabat, I will kneel and kiss the ground. I will arrive off the plane with my eyes open, not hooded as I was when I arrived here. It’ll be the first time I walk freely without shackles. The experience for me will be like the smile of a baby first seeing its mother.”

For me, it was Guantanamo Bay. For you, it might be rising carbon footprints, the wage gap in America or immigration conditions at the U.S.-Mexico border. No matter the issue, we all have a civic duty to educate ourselves AND to take action. Your voice matters because it isn’t just yours, but also of someone who cannot speak for themselves.

In the process of formulating a letter to the White House, I found myself very carefully picking apart different arguments and evidence to come up with an effective solution regarding Guantanamo Bay. Although the fate of my letter is not certain, having the ability to actually send them to the White House provided me with a sense of true, successful advocacy for an issue that is so close to home for me.

Ultimately, this is exactly what our representatives need—well-educated proposals from different perspectives (and this includes the youth of our country!) in order to make the decisions that matter most. As civilians, we cannot give Abdul Latif 19 years of his life back, but as well-educated students, we can work to achieve justice for the 35 detainees still imprisoned at Guantanamo.

Paper Managing Editor, Mishael Gill ’23 is all about helping people. She plans to advance into the pre-med track next year in college.

Currently,...