Weighted GPAs stifle course exploration, discourage study of arts and humanities

Due to the higher weight of AP and honors classes, many Staples students often compromise interest in elective courses for classes that stand to bolster their grade point average (GPA).

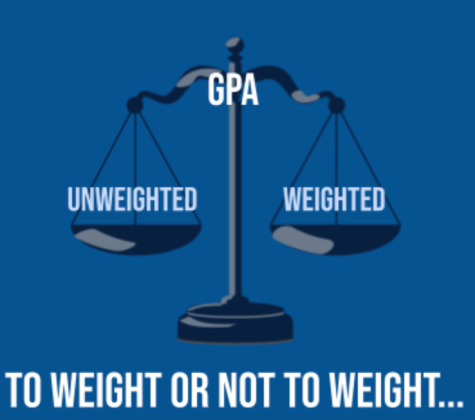

Reduced to the first few letters of the alphabet, the value of standardized test scores and other three-letter acronyms, students relentlessly seek to raise such figures through whatever means possible. This in turn eclipses a desire to learn—and perhaps more significantly the willingness to learn from failure. The most fear-inducing agglomeration of a student’s educational value: the GPA. A benchmark for academic success, to some students the GPA is an all-important, consequential and easily manipulated statistic. To balance the scales, students combine AP coursework with “easy A” classes to bolster their GPAs. This warped sense of academic value can be diminished in part with the elimination of the weighted GPA, which in turn would open the doors to the greater exploration of the comprehensive curriculum Staples offers.

When I perused the course catalogue prior to my freshman year, I was in awe of the long list of unique and interesting classes Staples had at its disposal, ranging from animation to zoology.

The use of the weighted GPA, however, places an inordinate emphasis upon course level, inhibiting students from taking electives and courses they are genuinely interested in. Staples is not alone in utilizing this statistic as 56% of high schools calculate a weighted GPA, per Educational Research Service.

On a 5.0 weighted GPA scale, a B+ in a college level course (e.g., AP, dual enrollment classes) is a 4.0 while in college and career preparatory classes (e.g., A, B, C level courses) the same grade is a 3.3.

Per the Staples Program of Studies, seven of over 90 elective courses, excluding gym classes, are honors or AP level. In such a competitive academic atmosphere, dozens of intriguing, niche, A-level classes are cast aside in favor of their more heavily weighted counterparts.

This system of evaluating academic rigor at Staples also works to the detriment of students with greater interest in the arts and humanities, disproportionately proving advantageous to students inclined to the sciences.

At Staples, the science and math departments combined offer seven honors classes and 10 AP-weighted classes. In contrast, the English and art departments each offer two AP courses, while English provides three honors classes to the art’s two. Between theater and music, there are no honors classes and a single AP course.

The discrepancies between advanced science courses and arts and humanities courses expands further. Between English, history and arts, the College Board offers eight APs altogether. Under science alone, there are seven AP courses.

Without the weighted GPA, an A-level class is worth the same as an AP course, and a portion of the pressure in partaking in every advanced class under the sun is dispelled. Furthermore, participation in elective classes will likely increase, as students will no longer contemplate a course’s impact on their weighted GPA and instead make decisions on subjects of intrigue.

Last year, I blended my interests in sports and English and enrolled in Sports Literature, Research and Composition, which examines the intersections of sport and culture, well beyond athletics’ entertainment value. Throughout the course, I never found myself to be disinterested, and instead found joy in each assignment, the nuance of the subject surprising me.

Opponents of the removal of the weighted GPA are quick to note colleges will evaluate students without this statistic differently as the difficulty of courses is not considered. However, most colleges will view a student’s grades exactly the same, as they recalculate academic rigor and success on their own scale. According to Ken Anselment, dean of admission at Lawrence University, to compare students from various high schools, curriculum and grading scales such an adjustment is necessary.

By removing one gas line that fuels the Staples pressure cooker, a variable that is a shallow representation of intelligence regardless, a student’s education will evolve into what it should be: an exploration of personal interests and the deepening of knowledge.

For Staff Writer Caroline Coffey ’22, journalism is in the family.

“My grandfather, [...] he wrote about the Boston Red Soxs, a Sports Reporter,...