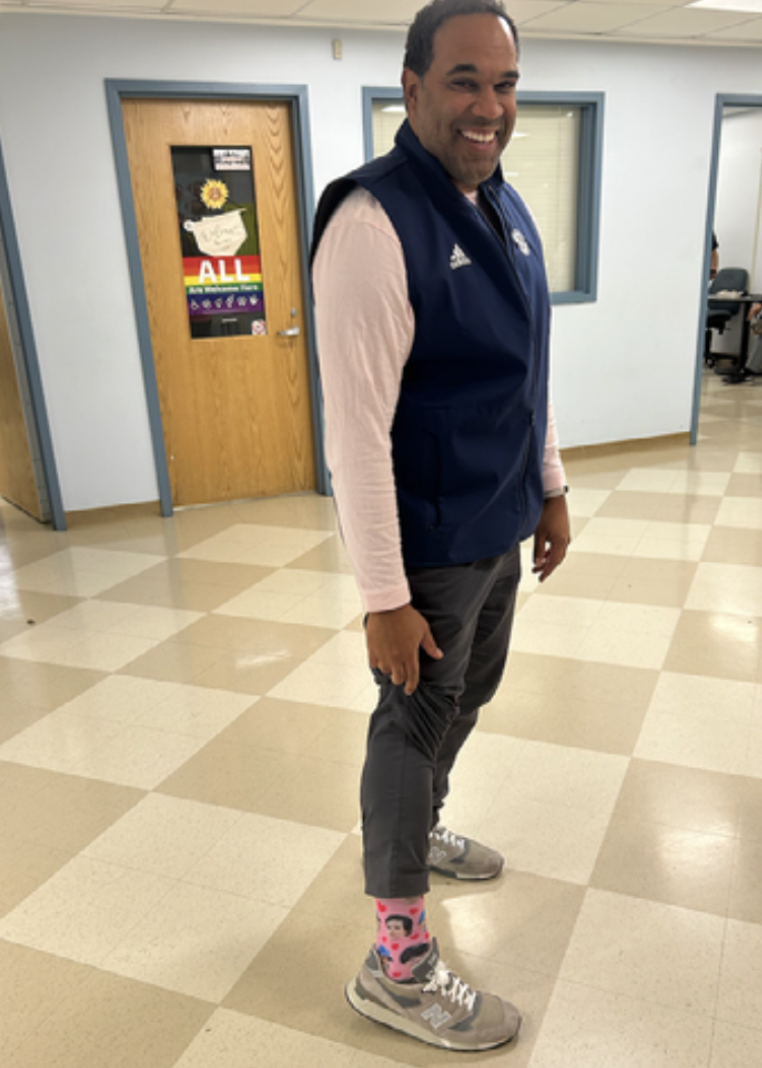

Paper Features: The story of our custodian—Williams finds faith through hardship

Jamaica

Reggae music filled the packed club and Sharon Williams was on stage.

“It was like me alone in the world,” Williams said.

“I would look, but I would not look into the crowd—I would look over the crowd. It was like I was in my own head.”

Williams was 21 years old at the time, living in Kingston, Jamaica and singing at a local club with her band.

While music would always be a constant in her life, almost nothing else in her life would be. Time would take her across

the ocean, through several careers, in and out of cities and eventually lead her to Staples High School, to work as a custodian.

Even years later, her Jamaican roots are apparent in every word she speaks. She talks with a heavy accent—rounded

words bobbing with a melodic cadence.

She grew up in Jamaica with music in her blood. Her uncle was Alton Ellis, an international reggae star. When

Williams was a child, Ellis would come visit Jamaica and the two would go to concerts together.

While the image of Jamaica—with its blue waters and vibrant music—evokes ideals of paradise, Williams’ child-

hood did not evoke the same peace. Her father left before she was born, and her mother, young and uneducated, sent Williams as a child from government school to government school.

“You felt like you’re not loved,” she said. “You felt like there was nobody there for you.”

Instead, she found solace in music. In her twenties, she formed a band with friends called “the Mighty Titans,” playing a regular gig at a local club.

Although she was in what she dubs the “fun part” of her life, Williams had three children and needed a way to support them. She wanted to give them the education her own mother never received.

“For me, I determined in my mind that I had to break away from this. I have to get through this, because I know that I’m capable to do better, and to do more,” she said. “So, I’m getting out of this.”

At 35, she decided to move with her family to America.

However, the moment she decided to leave her past behind, her past decided to find her.

Before leaving for America, Williams’ father returned to Jamaica. Williams had only ever spoken to him through letters, only seen photos of him when he was young. She had never heard his voice, never seen his face in person.

“I thought him coming from America—he’s supposed to look sharp,” she said. “I expected him to be dressed like in a nice suit.”

She pulled into the airport to pick him up, carrying a fantasy in her mind. But the man in the sharp suit was no-

where to be found.

“This man was standing at the post,” she said. “And I passed him about twenty times looking for my dad.”

He was scruffy, dressed like “a farmer.” Eventually, after wandering through the airport, she approached him.

“I go up to this man that’s standing there and I said, ‘Are you Oswald Williams?’” The man responded by calling out her nickname, Joy. It was then she knew she had nally found her father.

He stayed with her for three weeks—weeks in which their relationship both suffered and thrived under the weight of the past.

“I had a block up because I was still wondering why would he leave me as a child,” she said. “But after [he explained that] his mom sent him away and there was nothing he could do, then we started bonding.”

When her father had to go back to the Bronx, Williams decided to go back with him.

So, after belting reggae and living by the sea, after reconnecting with her father, after realizing there could be a better life an ocean away, Sharon Williams left for America.

America

Every night, Williams’ sleep was rocked by the pounding of train against railway overhead.

Her father’s home was beneath a train track in the Bronx, and Williams stayed there with her three children.

“I thought I was going to be an international singer when I moved to the States,” she said, chuckling.

But the path to fame was a mountainous climb in America. Instead, she took odd jobs, becoming a babysitter then a house cleaner.

While her jobs kept her occupied, she found her life lacked the community of Jamaica.

“I got to say, when I got here, I was filled with hurt and rejection and disappointment,” she said.

In 1994, she found her purpose. “My neighbor introduced me to the church and it was the best thing that’s ever happened to me,” she said. “You’re gonna make me cry, how much I love Him.”

Church allowed her to combine two of her passions: music and God. Her voice, which used to carry reggae melodies in a club by the sea, now belted gospel in a church.

Seeking job security, she ultimately took a job as a custodian at Long Lots Elementary School. Since then, she’s worked for years as a custodian at both Bedford Middle School and Staples High School.

“I broke away [from] the whole institution that’s caging me into being poor,” she said. “I’ve had my way and I’ve tried to accomplish.”

In fact, her determination has inspired her to attend business classes.

But, even in her pursuit to improve her future, she has kept pieces of her past with her always.

“If I had the money, I’d go back to Jamaica. It’s beautiful,” she said. “ The food is fresh and I lived right by the sea.”

But Williams, above all, has kept her faith.

“Along this way,” she said, “if your life doesn’t touch somebody’s life, then your living is in vain.”

This summer Margaux MacColl ’16 was cliff jumping in Africa. As she was preparing to jump, she looked around and realized that of the 200 people on the...