Anti-semitism at Emory disturbs Westport community

Yom Kippur is the holiest day of the Jewish year. It is a time of atonement, repentance and making amends. Ironically, many people say they will remember this year’s Yom Kippur as a day of intolerance and ignorance after students at Emory University spray-painted swastikas on the Jewish Alpha Epsilon Pi (AEPi) fraternity house.

The incident has both caught the attention of both the nation and more specifically, brought the issue of antisemitism into the Staples spotlight.

Anti-semitism, or hostility to or prejudice against Jews, is nothing new. But recent events have shined light on the subject and led many Westporters to reevaluate the presence of anti-semitism in their own community. Many students say that they have seen bigotry firsthand at Staples.

“The most prominent memory I have was when we were talking about the Holocaust in one of my classes, and the kid sitting next to me muttered under his breath that ‘the Jews got what they deserved.’ No one else heard him say it,” Sydney Sussman ’15, who spent three weeks in Israel and is actively involved in her synagogue, said.

There is a large Jewish population in Connecticut and in Westport, specifically. A recent study from City-Data.com shows that 6.3 percent of Westport residents are affiliated with Judaism, the second most populous religion after Catholicism.

This Jewish presence is evident in the community, whether through school days off allocated for religious holidays or the seven Jewish synagogues scattered around town.

Connecticut alone has a higher percentage of Jewish residents than the national average – in 2012, 3.2 percent of the state population identified as Jewish. In contrast, only 2.2 percent of the overall American population identified as Jewish, according to the Jewish Virtual Library.

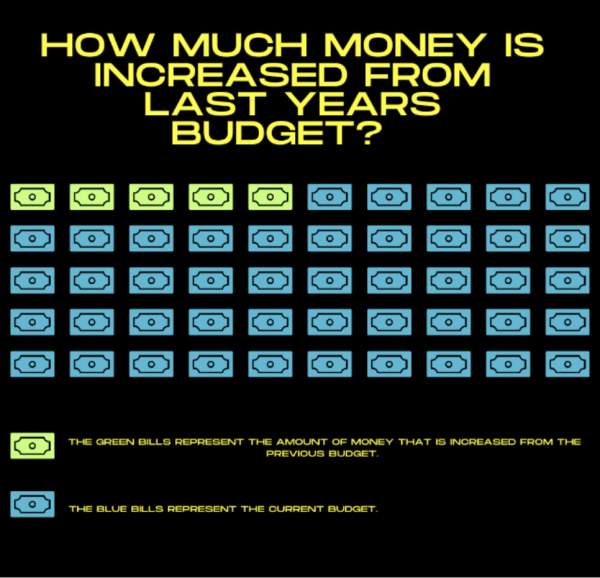

The Anti-Defamation League (ADL), an organization that works to stop anti-semitism and secure justice, reports that the number of anti-semitic incidents in Connecticut increased in 2013, while there was a decline in reported incidents across the U.S. in that year.

Thirty-one anti-semitic incidents occurred across the state, 18 of which involved harassment.

Many people, such as Sussman, believe that many of these incidents are due to the lack of education and awareness about Judaism, and the perpetuation of wrongful stereotypes.

“I think those students who are Jewish or pro-Israel should learn how to educate people who either don’t know anything or are actually against Jews, because more times than not, people who aren’t educated on certain topics just pick up knowledge on what they hear,” Sussman said. “And what they might be hearing isn’t always the most positive thing.”

In a survey conducted by the ADL, 70 percent of respondents who considered themselves anti-semitic said they had never met a Jewish person, and 35 percent said they had never heard of the Holocaust.

Caitlin Hoberman ’14, a current freshman at Emory University, agreed that spreading awareness is crucial in defying stereotypes and promoting tolerance, especially after the anti-semitic vandalism of the fraternity house.

“My older brother is in AEPi here, so I found out the night it happened,” Hoberman said. “Everyone on campus who I have talked to about it is really disappointed and upset that someone in our community would do that, but there have been campus talks against hate to combat any feelings of anti-semitism.”

Emory’s education and discussion-based response to the offensive graffiti is appropriate and significant, according to assistant regional director of ADL’s Connecticut office, Josh Sayles.

“Bad things happen in all communities,” Sayles said. “You don’t judge a community by the bad things that happen there but by how it responds to those incidents. The way I think you prevent anti-semitic incidents moving forward is for the community to speak up and band together to let everyone know that bigoted or anti-semitic behavior isn’t going to be tolerated there.”

Even students with no personal ties to Emory say the incident there has affected their view of anti-semitism at home.

“I think that the graffitied swastikas at Emory can impact people’s perceptions of anti-semitism and Judaism itself here by showing that outside of the bubble that is Westport, Connecticut, there are, in fact, large amounts of people who do not like Jews,” Sussman said.

Sayles, however, says there is a fine line between ignorance and intolerance, citing the hypothetical example of a swastika being found at Staples.

“It’s on a case-by-case basis,” Sayles said. “That could be targeting a Jewish person it could be anti-semitism. But swastikas are also general symbols of hate, and it could just be a knucklehead looking for attention who doesn’t really know what it means but knows it will get a reaction out of someone […] But it has the same effect on the students sitting at the desks whether it is intended to be hateful or not.”

Many students say they see these anti-semitic events as a chance to learn more about religion and intolerance on larger scale.

“I would [encourage] Staples students to learn about their religion,” Sarah Herbsman ’15, President of the Israeli Culture Club, said. “There is so much to learn, and the history can help you put modern day situations into perspective.”

The issue of anti-semitism is now on the radar at Staples, whether or not incidents have attracted widespread attention.

“You’re never going to eradicate hate,” Sayles said. “But what’s different from 40 years ago is that schools are not as outwardly anti-semitic. People who walk around in hallways know it’s not okay to call people a ‘dirty Jew’ or drop the ‘N-word.’ There’s plenty of bigotry, but the majority of bigots don’t want people to know that they’re bigots – and that’s a victory.”

Since the time that she could remember, Rachel Treisman ’15 always loved reading and writing. And with a long list of titles read, she kept track of...