Mob mentality and anonymity trigger belligerence at open house parties

By Molly Liebergall ’17

Two hundred pairs of stumbling feet stagger through the house with a nameless host. A once pristine home is now littered with half empty Solo cups, shattered glass and bits of drywall. As red and blue lights flood through cracked windows, 199 pairs of feet dash out the door; only one remains to grapple with the aftermath of his or her open house party.

The moment sirens begin to wail, many students react instinctually.

“When the cops show up, it’s just run and get away, find your friends and get to someone’s house,” an anonymous senior boy said. What he describes is more commonly known as the “fight or flight” response. During this split-second risk assessment, the brain releases stress hormones from the adrenal cortex, which is located along the adrenal glands that line the kidneys.

Long before the police arrive, however, the brain is constantly reacting to the surplus of stimuli that the open house environment offers.

Faced with the chaos of an overcrowded party, teens tend to succumb to a “mob mentality,” a psychological phenomenon causing their already underdeveloped adolescent brains to exercise even worse judgement. According to the American Academy of Neurology (AAN), the prefrontal cortex, which is the area of the brain responsible for judgement, decision-making and impulse control, is not fully matured until between the age of 25 to 30.

However, until development is complete, the brain must learn from the repercussions of trial and error.

“Teenagehood is a time of experimentation anyway, but you combine that with no supervision and a group mentality and […] you get the perfect storm,” Staples school psychologist Alycia Dadd said.

Within this “perfect storm” is the combination of an adolescent brain’s lesser judgement and the illicit “savagery,” as Keiran Simunovic ’16 phrased it, found at open house parties. Consequently, the mind becomes psychologically clouded.

“[The scene] becomes pandemonium because the energy is building […] and that’s when people sort of lose sight of not just who they are as people and as individuals, but they also kind of forget that empathetic edge that they have,” Jackson Daignault ’18 said.

At various house parties, Simunovic has witnessed actions similar in nature to those Daignault described, including the consumption of a pet goldfish and the destruction of a kitchen sink.

However, one gender may be more predisposed to acting physically belligerent at house parties than the other. Dadd explained that the reason for this is similar to the reason that car insurance rates tend to be higher for boys than for girls.

“[At a party,] girls might be more verbally impulsive,” Dadd said. “You might see girls say things that maybe they wouldn’t otherwise say […] whereas it might be more overt, physical impulsivity with boys.”

Since cars can be totalled by physical actions, but not by verbal actions, “that’s why [boys’] car insurance rates are high,” Dadd concluded.

Unfortunately, party hosts rely on a different type of insurance once the crowd grows and “people start doing things they might not normally do,” as Jack Schenck ’16 put it. However, the damaging outcome is much different when the crowd is smaller and more intimate.

“If people know the host, destruction of the home dramatically decreases because they’d have to face more consequences,” Harry Garber ’16 said. Partying among 200 students, only a handful of whom were originally invited to the host’s house, teens are cloaked in the anonymity of the crowd.

Yet this is not the first time Staples students have experienced the detrimental effects of the ability to hide one’s identity.

As previously evidenced by how some teens used popular apps such as Yik Yak or Whatsgoodly, anonymity often enables people to behave differently than they normally would, because they do not have to take responsibility for their actions.

Rider University professor of psychology, John Suler, refers to this phenomenon as the “online disinhibition effect,” which explains that online anonymity causes people to feel less inclined to act like themselves, or to respect the feelings of others. This theory has the same application to open house parties, explaining why Garber has witnessed partygoers punch holes in walls, smash beer bottles and steal food.

However, this type of misconduct at parties occurs less frequently than the generally respectful behavior that Staples instills in its students.

Dadd acknowledged that in Westport and said “There’s a lot of good kids, but it only takes one person to start it. Once someone does it, it can spread like wildfire.”

The solution to this, Daignault believes, is a moral that most people learn early on in childhood: treat others the way you wish to be treated.

“We have to keep teaching each other empathy and thinking about what it’s like to be in somebody else’s shoes,” Daignault said. “Take somebody else’s perspective before acting and doing something that’s destructive.”

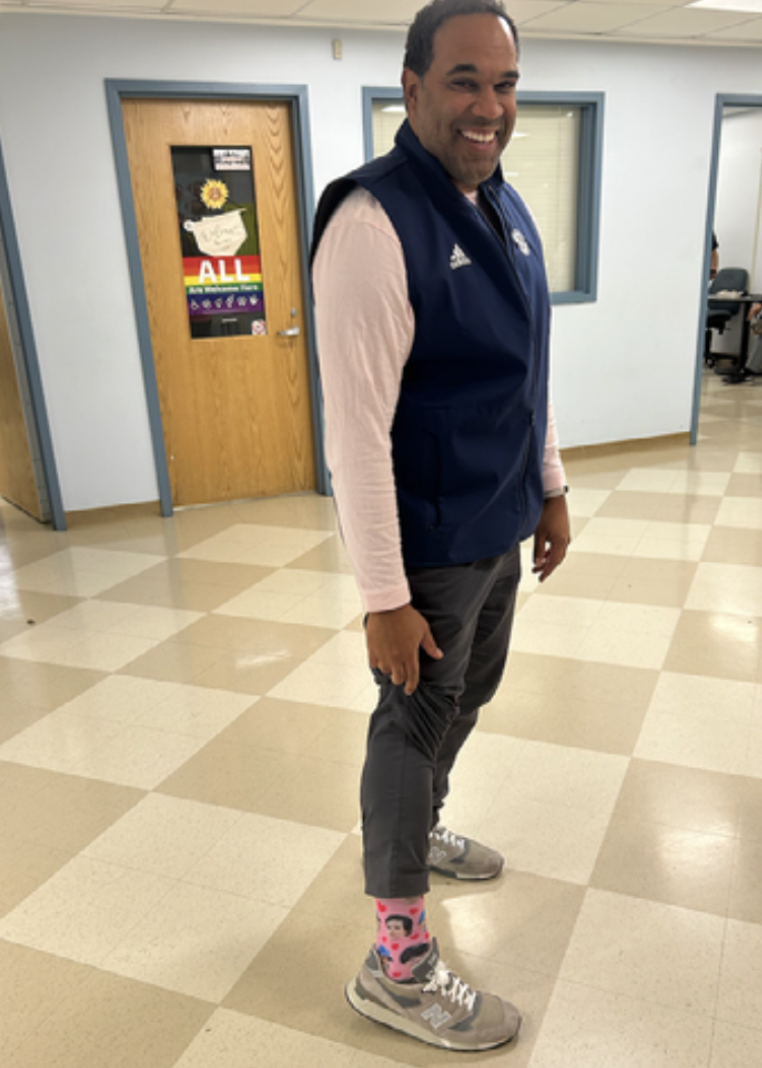

Molly Liebergall ’17, is someone worth getting to know. She is an intense soccer player, and plays for Staples girls soccer.

Inklings is one of molly's...